A shortage of pathologists for proper diagnoses is inhibiting progress on universal health coverage, a new Lancet series has highlighted.

They estimate there is just one pathologist for every one million patients in sub-Saharan Africa, a ratio 50 times lower than in high-income countries.

China, with one pathologist for every 130,000 patients, needs extra 70,000 pathologists to reach levels similar to the UK or US.

The series notes how a lack of laboratories, staff and basic medical tests results in misdiagnoses, inappropriate treatments and wasted resources in countries with already scarce resources.

Pathology ensures patients are correctly diagnosed and given appropriate treatment, but its inadequacy means treatment is presumptive.

The authors warn of the impact on patient care with patients poorly diagnosed or given inappropriate treatments, and of the wider impact on health systems.

“In Europe or the USA, we take for granted that if you see your doctor with symptoms of liver disease, you will be diagnosed based on a blood test, and given the correct treatment,” says Dr Kenneth Fleming, lead author of the Series, National Cancer Institute and University of Oxford, UK.

“Similarly, we wouldn’t dream of diagnosing breast cancer without performing a biopsy. But, in far too many countries around the world, diagnosis and treatment can be based on no more than a well-educated guess.”

Pathology services are the breadth of diagnostic testing needed to support health care.

They include specialties as biochemistry, microbiology, haematology, histopathology.

They also include imaging, and autopsies and forensic pathology to determine cause of death.

Pathology is considered a cornerstone of modern medicine.

It is central to detecting, treating and monitoring infectious diseases.

It is also key in noncommunicable disease, like diabetes, which cannot be detected on basis of clinical history or physical examination alone.

Cancer requires pathology for specific classification and staging.

Noncommunicable like diabetes and cancer account for 7 out of 10 deaths worldwide, and the rates are growing in low- and middle-income countries.

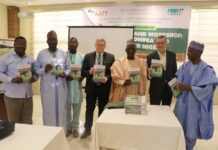

A recent estimate indicates Nigeria has just around 200 pathologists for its entire population.

And even fewer physicians trainees pursue postgraduate training in pathology.

The series estimates that at current rates of education and training, it could take up to 400 years for sub-Saharan Africa to match the pathologists-to-population ratio of the UK or US.

Professor Michael Wilson, Series author, Denver Health Medical Center, Colorado, USA says: “Our research has identified four key barriers which must be addressed, to ensure that pathology and laboratory medicine service delivery is optimal in re-source-limited settings: insufficient human resources and workforce capacity; inadequate education and training; inadequate infrastructure; and insufficient quality, standards and accreditation.”

The series suggests studies to determine the actual cost of pathology serives.

“Economic studies are essential to determine whether point-of-care testing is affordable, cost-effective, and an appropriate component of a well-functioning pathology system in resource-limited settings,” says Susan Horton, Series author, University of Waterloo, Canada.

“New diagnostic tests will be most relevant if they and their accompanying new treatments are within the financial reach of patients in low and middle income countries.”

The authors call on nations to develop national strategic laboratory plans to deliver at least a basic level of tests.

“We recommend that all countries should allocate at least 4% of their healthcare budget to pathology and laboratory medicine,” says Horton.

“Relying on out-of-pocket expenditures for diagnostics, leads to risks to health. Unless we have access to quality pathology services at all levels of care, achieving the year 2030 target of the SDGs, including universal health coverage will simply not occur.”

“There is an urgent need for nations to recognise that lack of access to adequate pathology and laboratory medicine services is a critical gap in health systems in resource-limited settings; without immediate and sustained intervention, this gap will only widen disparities between low and high income countries” says Dr Shahin Sayed, Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya and Secretary General of the College of Pathologists of East Central and Southern Africa.