In KK Park, on the Myanmar-Thai border, those who refuse to scam face torture, starvation and even murder. DW investigates one of Asia’s most brutal scam compounds.

https://p.dw.com/p/4bnQW

Copy link

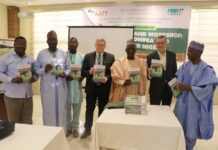

An aerial image shows KK Park on the Moei River

Thousands of people have been trafficked into KK Park, a compound on the Thai-Myanmar border designed for scamming people across the globe

Image: Stefan Czimmek/DW

Aaron couldn’t believe his luck. An up-and-coming tech company in Thailand was offering him a dream job — a high salary, great benefits, and a way out of a bleak future in southern Africa.

“I was hoping to go and work overseas. And one day, I was approached,” Aaron said. “I thought everything was legit — until I got to Bangkok.”

At the airport, Aaron was given a warm welcome and ushered into a car with two other young men from eastern Africa.

“We were supposed to go to a hotel that is maybe 10 minutes away from the airport. But we drove in a different direction.”

The driver drove for nearly eight hours before arriving in the Thai border city of Mae Sot, where Aaron and his fellows were trafficked over the Moei River and into a war-torn part of Myanmar.

“There were people with guns,” he remembered. “They said we should get in the boat — and we crossed.”

Aaron and his fellows were trafficked into a prison-like compound called KK Park. Here, thousands of people are forced into criminality — to scam people in the United States, Europe and China. The UN estimates that more than 100,000 people are being forced to work in scam centers in Myanmar.

DW’s investigative unit met with several survivors of the compound. They described widespread surveillance, torture and even weekly murders.

“We worked 17 hours a day, no complaints, no holidays, no rest,” said Lucas, a young man from western Africa. “And if we say we want to leave, they tell us that they will sell us or kill us.”

But who is behind this brutal operation?

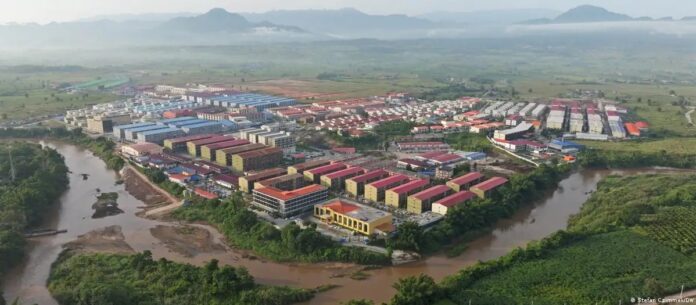

Satellite imagery shows how KK Park has grown since it first began construction in 2020

Satellite imagery shows how KK Park has grown since it first began construction in 2020

DW obtained satellite imagery that shows the development of KK Park. The image on the left was taken on February 18, 2020, the one on the right on January 17, 2024

Image: Maxar Technologies provided by European Space Imaging

Myanmar’s local enablers

We reviewed exclusive images taken from within the compound and spoke to several survivors who were held there. They all recognized the badges on the guards’ uniforms.

They are the insignia of the official Border Guard Force, a group of former rebels who stopped fighting the Myanmar junta a decade ago in exchange for free reign over their territories.

Their soldiers are present in KK Park. But the bosses of the operation are Chinese, according to several sources.

Tracing crypto to KK Park

We followed the money trail from several scammed victims to see where it leads. It took us to cryptocurrency wallets KK Park used to collect victims’ funds. From there, the funds were funneled to other wallets, which act like digital accounts and store cryptocurrencies.

One of those wallets was opened by Wang Yi Cheng, a Chinese businessman based in Thailand. He received tens of millions of dollars worth of cryptocurrency from wallets used by KK Park.

Wang is part of a larger network of overseas Chinese business people that ultimately leads to a notorious Chinese mafia boss.

At the time Wang was receiving direct transfers from KK-managed wallets, he served as the vice president of the Thai-Asia Economic Exchange Association, an association in Bangkok promoting Chinese and Thai relations.

Thai-Asia shares its building with the Overseas Hongmen Culture Exchange Center, which was raided by police in 2023, along with another Hongmen center in Bangkok, for operating illegally and serving as a front for Chinese organized crime.

Wan Kuok Koi smirks from the back of a police vehicle in MacauWan Kuok Koi smirks from the back of a police vehicle in Macau

Wan Kuok Koi, also known as Broken Tooth, is a former 14K triad boss who spent more than a decade in prison for his involvement in organized crime in Macau

Image: AFP/dpa/picture-alliance

The Chinese link

These organizations are closely linked to Wan Kuok Koi, alias Broken Tooth. He launched the World Hongmen History and Culture Association in 2018, an organization that has since been sanctioned by the US for its involvement in organized crime.

But Wan’s Hongmen organization also promotes Beijing’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a trillion-dollar infrastructure project meant to integrate China further into the global economy. It is also known as the New Silk Road.

“Wan Kuok Koi also has a quote that he uses fairly regularly: he says he used to fight for the cartels, and now he fights for the Chinese Communist Party,” Jason Tower, a leading expert on organized crime at the US Institute for Peace, told DW.

The area where KK Park was built is a target region of China’s BRI investments. Chinese government reports hailed development projects in the vicinity of KK Park as part of its BRI ambitions, though it later distanced itself from them following allegations of widespread fraud.

KK Park itself is not mentioned in official Chinese communications, nor did it hold groundbreaking ceremonies like other development projects in the area.

Instead, KK Park was purpose-built for scamming.

KK Park’s network expands

Bangkok skyline at sunsetBangkok skyline at sunset

Chinese criminal organizations have used Bangkok as a hub for operations linked to KK Park

Image: Stefan Czimmek

KK Park’s scamming operations trace back to a complex network of businesses and associations used by criminals to legitimize their crimes and launder millions in defrauded assets — and that network continues to expand from Southeast Asia to Africa, Europe and North America.

“We really see that these criminal networks are becoming more and more powerful, more and more influential, and more and more embedded in different countries around the world,” says Tower.

“And the efforts by law enforcement are only touching the tip of the iceberg.”

Find out more in our documentary ‘Scam Factory: Behind Asia’s Cyber Slavery.’

Aaron, Lucas and Laura’s names were changed for security purposes.

Edited by: Mathias Bölinger.